Read/submit comments to the Message Board

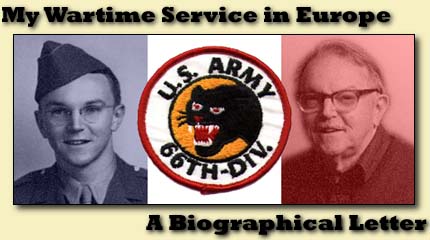

After seeing the film Saving Private Ryan, I felt a tremendous amount of respect for and gratitude toward the men of my father's generation. In a way, it's sad that it took a Hollywood blockbuster to force my generation to appreciate the sacrifices of his, and the millions who fought, suffered, and died to secure the liberty and democracy we take for granted today. The following is a long-overdue, modest tribute to my father, Richard C. Jewell, who in 1943, at the tender age of nineteen, enlisted in the United States Army. In the spring of 1994, I was finishing up a year of Spanish studies at the University of León, Spain. The fiftieth anniversary of D-Day was nearing, and huge celebrations were scheduled to take place throughout the French province of Normandy -- site of the Allied invasion. When I decided I would go there and join in the celebrating and homage paying, I asked my father to send me a summary of his experience during the war. I wanted to know his story in case anybody asked me why I had come to Normandy. My father sent me a detailed letter, photos, and related newspaper articles which I've gathered together here. I hope you enjoy them... * * * |

Dear Chris,

This is in response to your e-mail to Andrew of March 24 in which you asked for some details about my experience in Brittany during the war. To that end I will cover only briefly the periods before and after my wartime service in Europe.

Inducted at Ft. McPherson, Georgia, in March 1943 after graduating from high school in Gadsden, Alabama. Basic training and radio school at The Cavalry School, Ft. Riley, Kansas. Six months of academic courses in engineering in the Army Specialized Training Program at the University of Missouri (the ASTP was canceled when the Army discovered it needed plain old footsoldiers!). Advanced training and maneuvers at Camp Rucker, Alabama, with the 66th Infantry Division (Black Panthers). Because of my previous training at Ft. Riley, I avoided becoming an infantryman, but instead was assigned to the division's 66th Cavalry Reconnaissance Troop as a radioman and assistant driver in an M-8 armored car.

T/5 (Technician Fifth Class) Richard C. Jewell, seated in an M-8. |

The division set sail from New York on December 1, 1944. I was aboard the former British passenger liner M.V. Britannic, and we were in a large convoy guarded by destroyers. Landed in Southampton on December 12 and proceeded to Dorsetshire, where the Recon Troop was billeted in the little village of Puddletown (which was near Piddlehinton!). Our task before continuing on to France was to install 50-caliber machine guns on ring mounts atop the M-8 turrets, which normally carried a 37-mm cannon and a 30-cal. machinegun. Also, additional armor plate was added to the undercarriages of the M-8s.

In mid-December the Germans launched a counteroffensive which led to the Battle of the Bulge, and there was an urgent call for the 66th to head for the Western Front. Our infantry and engineers vacated their camp so hastily that they left complete Christmas dinners behind. (Our Recon supply people raided the abandoned infantry camp and returned with many rolls of toilet paper, a commodity in short supply.) As my troop was still upgrading the M-8s, the infantry left for France ahead of us.

On Christmas Eve, the bulk of the 66th Division was crossing the Channel on the S.S. Leopoldville when the ship was torpedoed by a German submarine a few miles off Cherbourg. We lost 802 men in that single night.

With the division thus decimated, we were in no shape for the Western Front. Thus, we were diverted to Brittany to replace the division stationed there, and those poor bastards headed for the heavy fighting in the Ardennes. It can be said that I might be alive today because of the deaths of those divisional comrades in the icy Channel waters.*

The Brittany front was created when Allied armies swept across France, cutting off some 50,000 German troops guarding the submarine pens at St. Nazaire and Lorient. Our infantry was assigned to those two sectors, while my Recon Troop was located in between at Carnac Plage at the head of the Quiberon Peninsula.

An M-8 light armored car. (Dad is not in photo.) |

We crossed the Channel on December 29 in landing ships so that we could drive our vehicles (which also included halftracks and jeeps) onto shore. Traveling in convoy and stopping overnight to sleep in tents, we reached Carnac on January 6.

The basic mission of the 66th was to prevent the Germans from trying to break out of their pockets, which they didn't attempt, anyway. As you will see from the enclosed Stars and Stripes article, our infantry and artillery did engage in some firefights with the enemy, as did the Free French Forces (FFI) in this sector. Where the Recon Troop was stationed the front was relatively quiet. We were billeted in various hotels around the area, mine being located just a few miles down the road from Plouharnel, which was a no man's land between the two forces (although we mounted observation posts in the attic of the town's schoolhouse). We maintained constant patrols and set up O.P.'s at night (one I remember was a depression behind rocks along the shoreline), from which, while hidden ourselves, we could watch the Jerries with powerful 'scopes. There was some shelling by the Germans directed at us, but I never experienced any. My platoon leader, a Lt. Brown, while on a reconnaissance mission immediately after we arrived in Carnac, was wounded by a German mortar shell and had to be evacuated to the States. We also lost a 1st lieutenant and a sergeant of the 3rd platoon, killed when their jeep ran over a German mine. As for me, I never fired a shot at the enemy! No heroics to brag about. The German coastal defenses on the peninsula included huge 340-mm French naval guns which sometimes fired shells as far as Vannes, some 20 miles away.

Victory parade through Quiberon. (Dad is at left, seated in car.) |

After the German surrender, their troops marched out of the peninsula, and we drove in triumph (so to speak) all the way down to Quiberon, greeted enthusiastically by the locals with flowers and streamers (see enclosed photo).

(I didn't know that I still had negatives of my wartime photos, yet by a stroke of luck I found them immediately, in envelopes neatly labeled by my father nearly 50 years ago! I had these prints made for you, as they are larger than the originals in my album.)

We left Brittany on May 20 and drove in convoy across France and up the Moselle River valley to the Rhine, arriving at the town of Bad Neuenahr, near Coblenz, on May 31. But our duty in the Army of Occupation was shortlived. In typical Army SNAFU fashion, 3 days later we headed back through the Moselle valley, then down eastern France, averaging 160 miles a day, until we reached Arles, near Marseille, on June 6. The division's new job was to operate a huge camp preparing other troops for departure to the war in the Pacific. (Of course, the dropping of the atomic bombs in August put an end to that mission.) I and a few other French-speaking buddies were picked for the plum job of being a military policeman in a small detachment in the lovely city of Toulouse, with no other G.I.'s present for miles around. Our job was to work with the French gendarmerie on border patrol and black market prevention, and the area we covered in jeeps was all of southwest France, from Bordeaux, Cognac, and Angoulême in the north, to Biarritz in the west, and down to the Spanish border. But this idyllic assignment lasted only from June 13 to September 4. Late that month, traveling in railroad freight cars, I headed for the Army of Occupation in Austria, arriving in the little town of Hallein, near Salzburg, on October 2. The following March, again traveling by rail, I was off to Le Havre and the ship home. I had just turned 22.

As you know from a Post article I sent you, you won't be seeing any wall in Normandy with my name on it! Maybe it will never be built. But I hope you will make that trip to the D-Day anniversary celebration anyway.

Lots of love,

Dad

* From a September 30, 2003 e-mail from my father: When units of my 66th Infantry Division were rushed across the English Channel on Christmas Eve 1944, we assumed that our destination was the Western Front, where the Battle of the Bulge was raging. Because the sinking by a German U-boat of the transport ship SS Leopoldville decimated the division, it was diverted instead to the relatively quiet sector in Brittany, replacing the 94th Division there. For years, veterans of the 66th, including yours truly, believed the above scenario, and I suspect many still do. I once read a report that the 66th was in fact assigned to the Lorient/St. Nazaire sector; when I questioned this, the author did not reply, so I assumed that he was in error. In June 2002 a friend in England sent me a detailed account of the Leopoldville sinking written by one Tonya Allen, whose great-uncle was killed in that tragedy. It states: "1,400 infantrymen had survived. ... The day after Christmas, the bulk of the survivors pitched camp on a racetrack on the outskirts of town (presumably Cherbourg—Jewell), where they spent a week. Then they moved on to Rennes, and finally to the Lorient/St. Nazaire perimeter, where 50,000 German troops were contained in two pockets. (Note: Most accounts never seem to mention my sector, the Quiberon Peninsula, held by the division’s cavalry reconnaissance troop!—Jewell) "There was little fighting in this area; in the next 5 months only 43 casualties occurred among the 262nd and 264th Regiments. It has often been thought that because of their vastly diminished size, these two regiments were diverted from their original destination (i.e., the Western Front—Jewell) and were instead assigned to the less dangerous duty at Lorient/St. Nazaire. If this had indeed been the case, then those who survived the sinking would actually have had it to thank for giving them a better chance of surviving the war. "However, official records show that it had already been decided to send the experienced 94th Division to the heaviest fighting at the Bulge instead, so the 66th had after all originally been destined for the Lorient duty. Thus, the sinking had no impact on the regiments’ assignment." |

|